“RAF Triumphs …

Raiders Chased Back …”

September 15th 1940

Battle of Britain

September 15th 1940 saw the last mass daylight attacks on London by the Luftwaffe and is now remembered in Britain as ‘Battle of Britain Day.’ From that day forward daylight raids became increasingly rare as Goering, Kesselring, and the Oberkommando der Luftwaffe realized that they were unable to suppress 11 Group Spitfire and Hurricane daylight defenses.

On September 15th the air battles were clearly visible to people looking up from below as in the case of this Dornier bomber which crashed into the forecourt of Victoria Station.

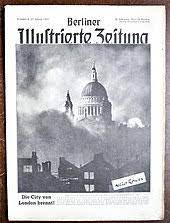

In another striking example of the propaganda war, the same photograph was used by the two sides to convey completely opposite positions. The photograph was taken by Herbert Mason of the Daily Mail in December 1940 and celebrated in Britain as a symbol of London’s survival in the face of mass bombing. The same photograph was used by the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung in January 1941 to prove that London had been reduced to ruins.

Much of my novel Infinite Stakes takes place on Battle of Britain Day in 11 Group’s Operations Room in Uxbridge, now preserved as the ‘Battle of Britain Bunker.’ This was Air Vice Marshal Keith Park’s 11 Group Headquarters from which he directed his fighter squadrons. By coincidence Churchill spent Battle of Britain Day there and saw the battle unrolling before him on the famous map table.

In his memoirs Churchill recalled that, as he sat there in the balcony overlooking the table, “The odds were great; our margins small; the stakes infinite,” from which I drew my title. At the height of the battle in the afternoon Park committed more squadrons. Churchill asked Park: “What other reserves have we?” Park replied, “There are none.”

Two days later Hitler cancelled his planned invasion of Britain.

In Infinite Stakes Eleanor is being interviewed and remembers Churchill’s question and Park’s reply.

Q: What exactly did Churchill say when he asked about reserves?

Park put down a telephone.

“Everyone is now airborne,” he said. “Nineteen 11 Group squadrons, the Duxford Wing from 12 Group, and two squadrons from 10 Group.”

A WAAF pushed the leading enemy marker into the Thames estuary and edged it toward London. A long line of Luftflotte II markers followed in its train. A group of RAF markers awaited them over Hornchurch.

“We are still, however, outnumbered two-to-one,” Park added.

“What other reserves have we?” Churchill asked him, staring down at the map table.

“There are none.”

“None? Did you say ‘none,’ pray tell me?” Churchill asked, as if unwilling to believe it.

“None, Prime Minister.”

Q: In his account in his History of the Second World War, Churchill wrote that Park looked ‘grave.’

A: I don’t think that’s fair. Park looked calm, as he almost always did. He made up his mind, positioned his resources, and then awaited the outcome. One must remember that we’d been doing this day after day after day. His stomach might have been in knots, but you’d never know it.

Churchill, on the other hand, was not used to seeing the fate of England—the fate, if you will, of the British Empire, from his perspective—laid out on a map table in real time, about to be decided in the next twenty minutes. I think he saw, for the first time, the scale of the threat and how thin our margins truly were. I think he saw all those markers scattered across the map, and realized there really were far more of them than there were of us. It shocked him, I think. ‘The few’ was not just a finely turned phrase: it was a mathematical fact.

I think he had been judging Park, sitting back and observing him, weighing him in the balance, as it were. Now, all of a sudden, I think Churchill realized that the only thing saving him from being Adolf Hitler’s special guest in Spandau Prison in Berlin was Keith Park’s judgment.

I hope these last few blogs have helped people to remember (or discover for the first time) the debt the world owes to the pilots who fought this battle, whom Churchill named ‘the Few.’ RIP