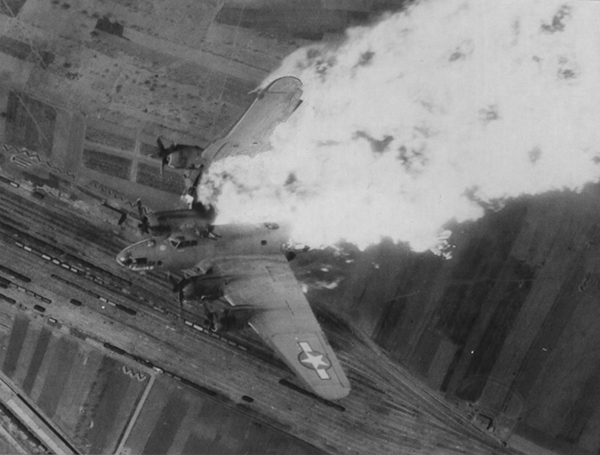

In 1943 Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda chief, called for ‘totalen Krieg’—total war—war without mercy, war without restraints—and in the skies over Europe he got what he wanted. The bombers of the RAF’s Bomber Command and the USAAF’s Eighth Air Force set out to destroy Germany’s war machine, and the Luftwaffe’s Reichsverteidigung—Defense of the Reich—fighters, mostly Focke-Wulf 190s and Messerschmitt 109s, rose to destroy the bombers.

In my recent blogs I’ve been looking at the evolution of the Allied bombing campaign against Nazi-occupied Europe in 1943, using three missions as examples: Operation Chastise, the RAF Bomber Command attack on three dams in the Ruhr valley, May 16th /17th; Operation Gomorrah, a series of incendiary attacks on Hamburg, July 23rd – August 3rd; and Operation Tidal Wave, the USAAF Eighth and Nineth Air Forces attack on the oil refineries at Ploiesti, Romania, August 1st.

Now I come to two final missions: Mission 84, an Eighth Air Force attack on industrial targets in Schweinfurt and Regensburg on August 17th, and Mission 115, a follow-up attack on Schweinfurt on October 14th, now known as Black Thursday.

The origins of these two missions lay in the Allies’ Point Blank Directive, which was issued following the Casablanca Conference between Roosevelt and Churchill in January, 1943. Point Blank was a plan to established Allied air superiority over Europe in order to permit an invasion to take place. A key element of the plan was to destroy Nazi Germany’s ability to build fighter aircraft.

The Targets

Regensburg, a city in Bavaria between Nuremberg and Munich, was the site of the largest Messerschmitt 109 fighter plant, and Schweinfurt, a city near Frankfurt, had Germany’s largest ball bearing plant. Severe damage to Regensburg would have an immediate impact on the Luftwaffe’s ability to defend Germany’s industrial heartlands and knocking out Schweinfurt would impact weapons production across the board.

The Plan

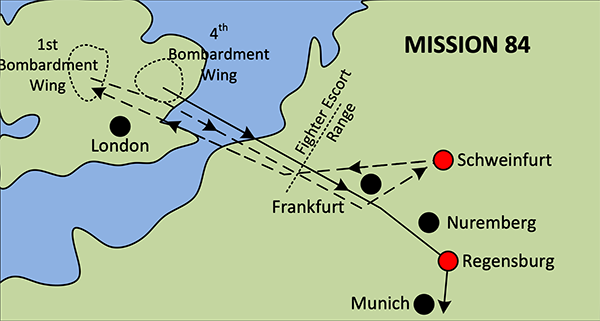

First, 146 B17 Flying Fortresses of the 4th Bombardment Wing, based in East Anglia, would fly to Regensburg in Bavaria to bomb the Messerschmitt factories there, and then continue south all the way across the Mediterranean to bases in Algeria. This flight plan would require them to face German defenses on the way to the target but not have to face them on a journey back to base.

Second, 230 B17s from the 1st Bombardment Wing, based in the English Midlands, would follow the 4th as far as Frankfurt before turning toward Schweinfurt. This second wave would be timed to arrive over Germany just as Luftwaffe fighters were back on the ground refueling and rearming after attacking the 4th Wing. Thus the 4th Wing was planned to have little opposition on the way out but would be subject to attack on the way home when the Luftwaffe would be refueled and rearmed.

It should be noted that the Allies had no long range fighters which could protect the B17s over Germany. The farthest the fighters—P38s, P47s, and Spitfires—could reach was the Belgian border with Germany, and only for a very few minutes. Therefore, the B17s flew in tight ‘box’ formations of up to 21 aircraft each to provide mutual defensive cover. Each B17 had up to 13 heavy 50-caliber machineguns and a box of 21 aircraft had more than 200 guns. However, the flight plan exposed the B17s to two hours of Luftwaffe attacks.

It should also be noted that it was extremely difficult to assemble tight formations of B17s which were not easily maneuverable. Indeed, the mission plan allowed for up to 90 minutes just for the bombers to be shepherded into their mission boxes.

Mission 84

Fog delayed takeoff by almost two hours and other scheduling complexities meant that the 1st Wing was almost 3 hours behind the 4th Wing, instead of right behind it, meaning that the Luftwaffe did not have to split its forces between the two wings.

The 4th Wing, led by Curtis LeMay, succeeded in reaching Regensburg, although with the loss of 15 aircraft shot down, and successfully bombed the Messerschmitt factories before escaping southwards across Switzerland. However, Me 109 production quickly recovered: Regensburg produced 2,100 fighters in 1943 but over 6,000 in 1944.

The larger 1st Wing, with 230 aircraft in 12 boxes, arrived over Germany to face the full brunt of the Luftwaffe’s rearmed defenses. The ball bearing factory at Schweinfurt was damaged but heavy smoke soon obscured the target and reduced accuracy. Overall production and inventory of ball bearings was not seriously reduced, resulting in the second mission months later.

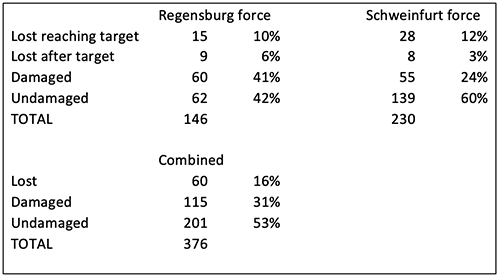

The Toll

In total for both targets the Eighth Air Force lost over 500 airmen of whom approximately half survived to become Prisoner of War. They lost 60 aircraft destroyed and almost twice as many damaged, and many of the damaged aircraft were beyond repair.

Mission 115

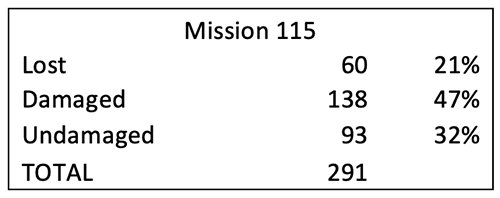

Losses from Mission 84 were so severe that the Eighth Air Force did not return to Schweinfurt for two months. When it did, with 291 B17s on October 14th, the results were even more catastrophic. The ball bearing factories were damaged but returned to full production after 6 weeks, and the Eighth Air Force’s losses were even more severe than before, with 21% of the aircraft lost.

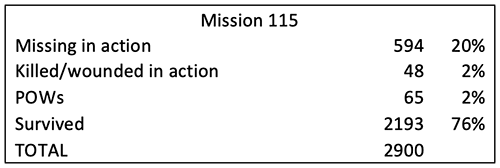

Casualties among the aircrews were correspondingly awful.

The Aftermath

Mission 115 became known as ‘Black Thursday.’ It was clear the flying unescorted B17s (and B24s) over enemy-held territory in daylight resulted in unacceptably high losses. No major new missions were attempted until the following February, in a campaign known as ‘Big Week.’ By now the bombers were escorted all the way to the target and back by P51 fighters equipped with long distance tanks. At last the Eight Air Force had fighters as good as the Luftwaffe’s Fw 190s, and had them throughout the mission.

Afterthoughts

One of my favorite songwriters is the late, great Kris Kristofferson, and one of my favorite songs is ‘Bobby Magee.’ But, with due respect to Kris, the lyric includes a profound error:

Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose

Nothin’ ain’t worth nothin’ but it’s free.

But our freedom isn’t free. It might be free to us, but only because it was already bought and paid for long ago by the air crews of Missions 84 and 115, and all the other aircrews who flew all the other missions. RIP.