I remember being in school 70 years ago on February 6th, 1952, at Gordonbrock School near Ladywell in South London. We were called to assembly and told that King George VI had died and that Princess Elizabeth was now Queen. We knelt on the floor and said a prayer for his soul, and another for the new queen. We were then sent out to the yard for playtime.

I do remember it was raining and I had wet feet. Someone said we shouldn’t run or play as usual, out of respect for the occasion, so we stood in the rain catching sniffles. I also remember coming face-to-face with the reality of death, because he was the first person I knew who had died. (It is typical of the role of the monarchy in those days that we felt that we knew the king personally.) It was my introduction to mortality: if the king could die anyone could, including me.

I also remember the astonishingly quick pivot from the past to the promise of the future in the words of the proclamation:

“The king is dead. Long live the queen!”

Winston Churchill, who was Prime Minister at that time, encapsulated that immediate transition as you can hear here.

The Queens of England

In celebration of the 70th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth’s accession to the British crown, I thought it might be interesting to recall England’s other regnant queens.

You can become Queen of England in two ways—you can inherit the throne, as Elizabeth did, and be the monarch in your own right (a ‘regnant’ or reigning queen,) or you can marry a prince who becomes king, as Kate Middleton has done.

There have been approximately eight regnant queens—I say approximately, because some are disputed. So, in a brief potted history, here are Queen Elizabeth’s forerunners.

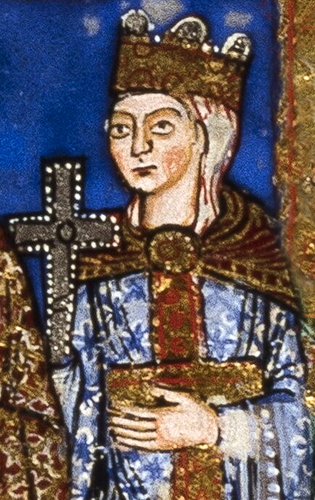

Matilda

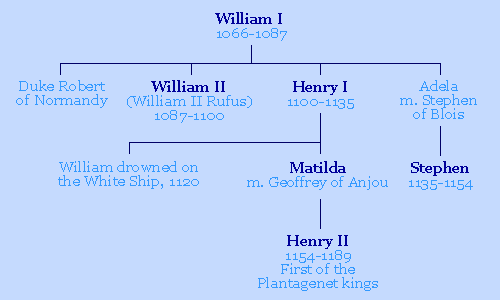

I’m starting with Matilda, although many wouldn’t. She was the oldest daughter of Henry I and the granddaughter William I (William the Conqueror.) She was born in 1102 and in 1114 she was married off to the Holy Roman Emperor, becoming the Empress Matilda at the age of twelve. (The Holy Roman Empire was not Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire, but that’s another story.) The Emperor died in 1125 and she was married to a powerful French nobleman, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, in 1128.

Matilda’s brother William, heir to the throne of England, died in the controversial White Ship disaster (another story) and Henry I named Matilda as his heir. However, when Henry died in 1135 her cousin Stephen of Blois, another of William the Conqueror’s grandchildren, seized the throne and had himself crowned king in Winchester Cathedral.

Matilda began a civil war against him that ebbed and flowed for almost 20 years—both Stephen and Matilda were captured at various stages of the conflict—a period now known as The Anarchy. Stephen was powerful and capable and held the upper hand. He was considered well-mannered and courteous whereas Matilda was considered arrogant and overbearing.

It is therefore a testimony to Matilda’s determination and political skills that she was able to fight him to a stalemate over the next 20 years, escaping many disasters, and outlasting him. The dispute was finally settled when Stephen agreed to name Matilda’s son as his heir instead of his own son. Stephen died in 1152 and Matilda’s son, known as Henry FitzEmpress, became Henry II, the first of the Plantagenets and one of the greatest of all mediaeval kings.

She died in 1167 at the grand old age of 65 (the average life expectancy of a woman was in her mid-30s) in the midst of her son’s very successful reign. She was never crowned queen, usually being referred to as Domina Anglorum (Lady of the English,) but she ruled parts of England in her own name and, as the daughter of a reigning king and the mother of another, having fought successfully to preserve that lineage, I think she deserves to be counted as the first Queen Regnant of England. To historians who tend to treat her as a minor figure I say: ‘you try being a woman in the 12th century with your rightful inheritance stolen, and let’s see how well you do!’