In my new book, Trial and Tribulation which will be published on June 6th, my protagonist Eleanor is deeply involved in the conferences that shaped Allied war strategy in 1943. These conferences were driven by the hopes and needs of three radically different men in three radically different circumstances: Franklyn Delano Roosevelt, Winston Spencer Churchill, and Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin.

The evolving strategic situation

At the beginning of 1943, when Trial and Tribulation begins, Stalin and Hitler were engaged in a titanic fight to the death along a thousand-mile battlefront running north and south through Russia, from the Baltic in the north to the Black Sea in the south. The battlefront was a meat grinder consuming vast quantities of men, equipment, and supplies, directed by two men, Hitler and Stalin, who shared an utter disregard for human life. The campaign had reached a crucial moment at Stalingrad in a battle that would determine the trajectory of the entire front and the momentum of the war in Europe.

Meanwhile the Anglo/American Allies were in the process of clearing Hitler’s and Mussolini’s troops from North Africa, an important but not decisive strategic battleground.

What Stalin needed desperately was a second front somewhere in Nazi-occupied northern Europe, an invasion by American and British forces that would force Hitler to transfer men, artillery and particularly aircraft back from Russia to defend against this new ‘second front.’

Stalin did not get a second front. What he got was an Anglo/American strategy aimed at striking north through Italy, which was considered less risky than attacking through northern France or the low countries. Italy was, they said, ‘the soft underbelly of Europe.’ Churchill and Roosevelt, one can argue, were focusing their attention on the wrong side of the Alps and happy to let Stalin soak up Hitler’s resources.

What Churchill and Roosevelt did offer Stalin was an intense bombing campaign against Germany, which they promised would so damage Hitler that it would constitute a ‘second front’ in its own right. This commitment shaped the air battle over Europe in 1943 and much of 1944.

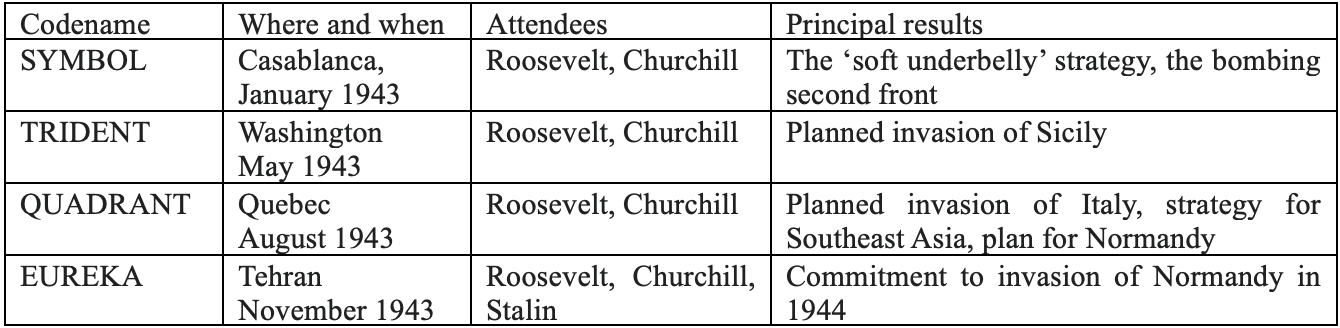

The Conferences

There were four principal conferences in 1943, the first three of which are described in Trial and Tribulation when Eleanor is a fictious attendee.

Stalin

Stalin came from very humble circumstances, a mere ‘provincial’ from Georgia, but worked his way up through the ranks of the pre-revolutionary Bolshevik/communist party and seized his moment when Lenin died in 1923. He combined Marxist/Leninist pseudo-scientific history and communist theory with an authoritarian cult which offered obedience or death.

By the time World War II started Stalin was the absolute ruler of Russia, governing through a highly efficient totalitarian police state apparatus. He initially agreed with Hitler to divide up Eastern Europe between them (Russia grabbed half of Poland, a good chunk of Finland, and all of Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia) and was shocked when his ally Hitler reneged and invaded Russia in August 1941.

As my book unfolds in 1943 Stalin survives the battle of Stalingrad and begins the process of marching implacably toward Berlin.

Churchill

When the war started Churchill was a has-been on the margins of influence, a man too extravagantly gifted, too mercurial, too idiosyncratic, to be a leader. He was an aging memento of the reign of Queen Victoria, a leftover Imperial artifact. He had spent the 1930s out of government bemoaning the rise of Hitler and Mussolini and attacking the political establishment for not doing anything to stop or even slow down fascism.

In 1940, following the disastrous defeat of the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk, it was universally assumed that the British would have to sue for peace. It was only a question of how much they’d have to give Hitler for him to let them survive. Churchill was selected to lead a multiparty unity government but took Britain in a completely different direction. Armed with little more than his oratorial skills (and a couple of hundred Spitfire and Hurricane fighter aircraft) he declared that Britain would never negotiate and would fight to the death. “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender …”

He even told his cabinet colleagues that he expected them to literally die fighting: “If this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.”

By the time this book takes place Britain has survived three long and painful years of war, but at the cost of hollowing out the British people and economy, Britain’s armed forces were shrinking, as was the economy, and the British Empire were beginning to crack under the strain.

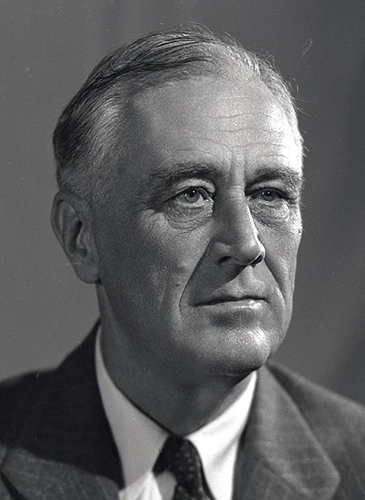

Roosevelt

Roosevelt was a New York politician who came from a wealthy and well-connected family (his cousin was President Teddy Roosevelt.) He ran unsuccessfully for the Vice Presidency in 1920 and successfully to be Governor of New York in 1928. He was elected President of the United States in 1932, in the depths of the Depression and successfully instituted the ‘New Deal,’ created Social Security, and led many other liberal (in the traditional American sense of the term) initiatives.

His political success was even more notable given that he contracted polio in 1921 and was paralyzed from the waist down.

He had established an absolute domination over presidential politics by the time the United States was attacked at Pearl Harbor in 1941. From being reluctant to become involved in the war (although sympathetic to the plight of Britain and Russia) he swung abruptly and masterminded the process by which the American economy, by far the largest in the world, was converted to the greatest ‘arsenal of democracy’ in the history of the world.

The Three Together

So, there they are. Front right to left as they pose in amity are: the ruthless dictator on his way to conquering half of Europe; the omnipotent President at the height of his domestic and global power yet trapped inside a wasting body; and the aging parliamentarian living, for the most part, off his words.

When the war ended a few months later in August 1945 only Stalin was left in power; Churchill had been defeated by a landslide in a general election and Roosevelt was dead.

Eleanor’s Analysis

My character Eleanor sees these men not so much as partners as competitors in a race to dominate Europe. In this race she sees Churchill as an also-ran.

From Trial and Tribulation in Casablanca in January 1943:

Everyone’s working assumption was that once the war was over the Allies would go home and leave the liberated countries of Europe to haul themselves back onto their feet and pursue their own destinies; thus, for example, Poland would be returned to the Polish people who would elect a new government of their choice. Germany would be purged of Nazis and left to rot.

Eleanor didn’t believe a word of it.

The Americans wouldn’t want to take over Europe—it was far more trouble than it was worth—but the Russians would feel it was their destiny to bring the bounteous benefits of Soviet Communism to the west. The Russians would not return a square inch of territory to its rightful owners.

The entire war in Europe, she thought, was a race between Russia and America to see who could occupy as much of Europe as possible. She doubted Roosevelt saw it in such clear terms and Stalin was too busy fighting for his life, but if Stalin broke the German 6th Army at Stalingrad she had no doubt he would see the opportunity and grasp for it.