This is the third of three blogs devoted to aircraft that were not as quite successful as some of their contemporaries, but which fought to the limit of their abilities and deserve honorable mentions in the annals of aviation history. This time it’s the Grumman Martlet—not a household name but a dogged fighter, the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm’s version of the American F4F Wildcat.

At the beginning of World War II the FAA had a collection of obsolescent aircraft, most notably two types of biplanes: the Gloster Sea Gladiator fighter and the Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber. In spite of their weaknesses and the fact that they were outclassed by enemy monoplanes these aircraft fought magnificently and far exceeded all hopes and expectations.

The FAA desperately needed a modern monoplane fighter. For a variety of supply and technical issues naval versions of the Spitfire and Hurricane, the Seafire and Sea Hurricane, were slow to be developed and not widely available until later in the war, nor could they be flown off short deck escort carriers. The FAA therefore turned to an American aircraft, the F4F Wildcat, which they renamed the Martlet.

Martlet: Origins and design

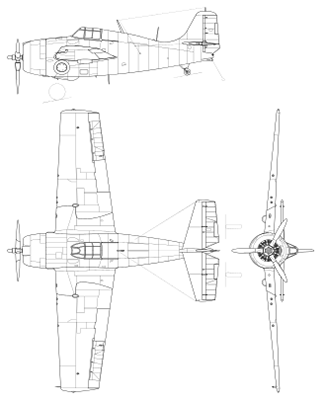

The Martlet was the Fleet Air Arm’s name for the F4F Wildcat. The F4F was developed by Grumman in the late 1930s to US Navy and Marine Corps specifications and entered production in 1940. It was small and tough, both essential qualifications for carrier aircraft. It was powered by the excellent Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp 14 cylinder radial engine—the most produced aircraft engine in history, which also powered many other aircraft such as the DC3 and the B24. The Martlet had four 50-caliber machine guns—a respectable amount of firepower for the time.

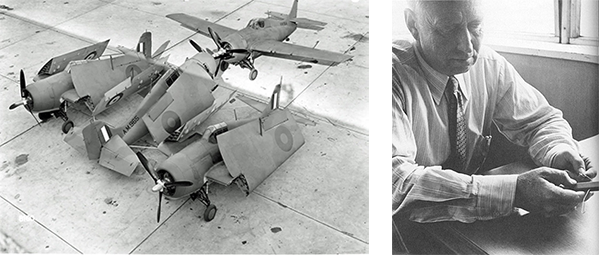

The Martlet also had the remarkable ‘Sto-Wing’ folding wing design which meant that it could fit into small elevators and be packed on cramped flight decks and hangar spaces: five folded Martlets could fit into the space required to two unfolded Martlets, as this publicity photograph shows.

Martlet: Operations

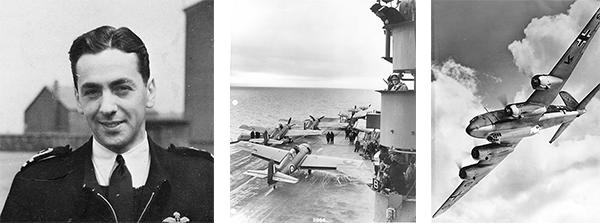

The Martlet began operations serving in the Malta convoys in the Mediterranean in 1941, operating from the tiny escort carrier HMS Audacity, which had a flight deck only 420 feet long and no hangar deck. The Martlet immediately proved its value by shooting down an Fw 200 Condor—and four more on the next voyage! (Condors were long-range German reconnaissance aircraft that would search out convoys and shadow them—these were the days before reliable radar.) Two of these victories were won by Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown, the astonishing FAA pilot I will write about in a future Breaking Point novel.

I would still assess the Wildcat as the outstanding naval fighter of the early years of World War II … I can vouch as a matter of personal experience, this Grumman fighter was one of the finest shipboard aeroplanes ever created.

Martlets fought until the very end of the war. In March 1945, they shot down four Messerschmitt Bf 109s over Norway, the FAA’s last Wildcat victories.

Martlet: Slender Thread

In A Slender Thread my protagonist Johnnie Shaux flies a Martlet from an imaginary fleet escort carrier HMS Nonsuch. They are part of an imaginary convoy from Gibraltar to Malta in August 1942 I called Operation Podium in honor of the men who fought in the real Operation Pedestal.

When he first sees the Martlet it reminds him of his dog, and he immediately decides that he will like it.

The Martlet was not an elegant aircraft, Shaux thought. It had a big, bulbous nose encasing its Twin Wasp engine and a short stumpy tail, with none of the smooth lines and graceful curves of a Spitfire; a bulldog rather than a greyhound. No, Shaux thought, not a bulldog but a Bouvier: Charlie has a big nose and a stumpy tail and he looks just fine. He decided, quite irrationally, that he would like the Martlet, and think of it as a Bouvier like Charlie.

Within a minute the fitters were explaining the exact workings of the hinging and locking mechanisms, while Shaux admired their elegantly and deceptively simple design. Some expert draftsman at the Grumman factory on Long Island in America had conceived them and drawn them at his drafting table; skilled metal workers had fabricated prototypes; doubtless they had been tested and redesigned and refabricated many times until a final version, the progenitor of this one, was exactly right. Then, just to complete the process, some advertising chap in a smart suit in the front office had dreamed up the name ‘Sto-Wing.’

In real life the Sto-Wing was invented by Roy Grumman, the founder of Grumman Aircraft, using paperclips and a pencil eraser—an act of engineering genius.

Back in the world of A Slender Thread, Shaux learns to master the most difficult challenge in carrier operations: the deck landing.

He made a banking turn toward the end of the runway where Lingard stood, with his white paddles clearly visible. Surely he was too low? Lingard’s paddles were raised above his head—Shaux was too high! Damn! Cut the revs, raise the nose. Paddles down—too low, damn it! Just a few revs more.

The trick, Shaux suddenly realized, was not to simply respond to Lingard, which would always make him too jerky, reacting and correcting the last mistake, but to look at the runway and come down the glide path—the slot—as he normally would, using Lingard for confirmation, not instruction. Raise the nose. Lingard’s paddles rose to the slot position. Good. Ease her down…lift the nose a trifle but not too much…almost down…paddles still outstretched…almost down…almost down…it looked as if he was almost going to cut Lingard in two with his right wing…

Paddles in ‘cut’ position. Throttle to idle. Nose up to let the hook drag down. Right wing flashes past Lingard—damn, that’s close!

BANG!

The hook snagged one of the arresting wires and the Martlet was caught just as a fisherman catches a fish. The wires screamed out to their limits and stopped the Martlet in its tracks. Shaux was flung forward violently in his straps, with his nose stopping just short of the gunsight, as the Martlet decelerated from 60 mph to zero in twenty feet.

Wow! Shaux felt as if he had just driven his aircraft into a brick wall. He pushed the canopy open, catching his breath. Wow! Lingard appeared on the wing beside him.

“How did I do, Lingard?” There was no point of pretending to be calm and casual.

“Not bad, sir.”

“I thought I was going to hit you.”

“Missed me by a mile.”

“Let’s do it again.”

I hope you’ll enjoy A Slender Thread.