September 6th Eighty-One Years Ago

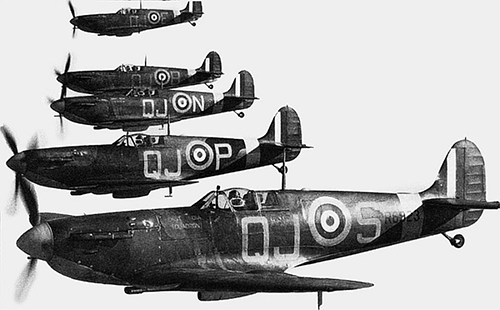

Eighty-one years ago today the fate of Europe—indeed the fate of the world—hung in the balance. The Battle of Britain was raging over southern England. The Luftwaffe had been unable to defeat the RAF, despite the Luftwaffe’s clear numerical advantage and the dogged determination of their brave aircrews. The embattled Spitfire and Hurricane pilots of RAF Fighter Command’s 11 Group—nicknamed by Churchill as ‘The Few’—simply refused to give up.

On September 6th, Herman Göring, commander of the Luftwaffe, frustrated by the failure of his forces to crush the RAF, decided to change tactics, and launch a direct assault on London itself. It was to prove a fatal error…

From my novel Breaking Point:

0 hours, Friday, September 6, 1940

RAF Oldchurch, Kent, England

Johnnie Shaux awoke an hour before dawn. His tiny cubicle smelled dank, like the cellars beneath the orphanage, leavened with just a faint, almost undetectable whiff of horse manure. He pulled his uniform on by feel in the darkness and fumbled his way into his heavy sheepskin flying boots, still half-asleep, unshaven and unwashed.

Outside the hut the night was still as black as pitch; there were no stars, and the air smelled of rain. He waited until he could detect vague gradations of blackness, yawning and rubbing his eyes, and set off to walk along a crudely fashioned wooden walkway beside a long row of huts. The breeze was warm and soft, and from the invisible woods that bordered the field he heard the first tentative chirpings of the predawn chorus.

He reached a larger hut, barely visible in the gloom, its windows tightly sealed with blackout material. When he opened the door, the glare of naked light bulbs dazzled him. An airman silently handed him a mug of hot, sweet tea, and Shaux retreated back out into the darkness. He felt his way to a decaying deck chair on the veranda and sat down. The tea scalded his tongue. He lit a cigarette, and the smoke tasted harsh and acrid in his mouth.

He sat with his eyes closed, gathering his senses, stretching his limbs one by one, taking an inventory of his brief life, wondering whether he would still be alive to do so tomorrow. Every day was the same, endlessly repeated. “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose,” he muttered under his breath. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Yesterday had been a bad day, although no worse than the day before or the one before that. Each morning the bombers gathered in the skies over northern France and Belgium like a swarm of locusts. Above them rose the 109s, like clouds of angry wasps. Then they swept across the Channel, wave after wave. The first wave of bombers would swing toward some hapless 11 Group airfield, the second toward another, and so on, each wave carrying at least forty tons of high explosives to rain down on its appointed target, Manston or Lympne or West Malling or Hawkinge or Oldchurch…

Squadron by squadron, 11 Group would scramble in response to the RDF blips that foretold the coming of the enemy, climbing hard with throttles wide open and the Merlins screaming, clawing up through the thinning air, “hanging from their propellers” as the pilots said, climbing fifty vertical feet every second while crossing three hundred feet of the ground far below them; turning to the vectors given them by the tinny voices of the controllers; staring into the haze above them, trying to penetrate the incandescent blaze of the sun, desperate to see the enemy before the enemy saw them.

After four or five minutes they’d be at the altitudes favored by the lumbering bombers, but at a ground speed of only two hundred miles per hour while they were climbing at an angle of fifteen degrees, the Spitfires couldn’t catch the bombers even if they saw them.

They’d continue to climb, wondering why the Merlin, spinning at forty revolutions every second, powered by five hundred controlled explosions of compressed high-octane gasoline vapor in its twelve cylinders, didn’t shake itself apart; or wondering why the tips of the propellers, slashing their way through twelve hundred feet of air each second, a mile of air every five seconds, did not disintegrate.

In another three or four minutes—if they were granted that eternity—they’d be entering the thin, cold air above twenty thousand feet, the realm of the 109s, the angry wasps, each armed with three vicious canons capable of sawing a Spitfire in two.

And then what? Would there be nothing but empty sky with the controller’s calm voice vectoring them back and forth and round and round in a futile search for an enemy that wasn’t there? Or would there be a sudden, heart-stopping bang–bang–bang as the black silhouettes of 109s erupted out of the sun, canon shells ripping at the Spitfires?

And then what? A split-second chance to pour the contents of the Spitfire’s eight machine guns into some hapless or inexpert enemy, stitching holes in his wings or his fuselage or chiseling bits off his engine or the pilot’s body? Or would there be an eruption of oily smoke and flame from the Merlin, the heat of exploding high-octane fuel burning through the absurdly thin fire wall ahead of the cockpit? Or the surreal feeling of dead controls if the cables were cut by canon shells, utter helplessness as the Spitfire stalled and dropped like a spinning stone, converted in a split second from an elegant flying machine into six thousand pounds of scrap metal at twenty thousand feet in the sky with nothing to hold it up? Perhaps a panicked escape from the doomed aircraft, perhaps wounded, perhaps burned, perhaps blinded, into the sudden roaring of the frigid sky, dependent on a parachute that might or might not open and that, even if it did open, might or might not have been damaged by canon fire or flames?

Shaux started; his cigarette had burned down to his fingers. He flipped it away and lit another.

The Royal Air Force station had gradually awoken around him. A truck growled to a halt nearby, disgorging members of the ground crew. Shaux could follow their movements by the flickering of their electric torches and the muttering of their sleepy curses as they checked the aircraft parked around him.

Well, yesterday had been a bad day. Perhaps today would be better; perhaps not. No man controlled his own fate; resisting fate led to despair.

He knew it, accepted it, bowed to its inevitability; he just wished that fate could bloody well get it over with…