Edward R Murrow, the great American journalist, said of Churchill: “He mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.” Churchill himself, years later on his 80th birthday said, with uncharacteristic modesty: “It was the nation and the race dwelling all round the globe that had the lion’s heart. I had the luck to be called upon to give the roar.”

The speeches Churchill gave in May and June, 1940, still ring clearly through the intervening eighty years.

It all began on May 13th, when he had been in office a mere three days, and when western Europe was collapsing helplessly against the juggernaut of Hitler’s blitzkrieg, that Churchill told the British people he had nothing to offer but “blood, toil, tears and sweat.”

He went on to say:

You ask, what is our policy?

I will say: It is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark and lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our policy.

You ask, what is our aim?

I can answer in one word: Victory. Victory at all costs—Victory in spite of all terror—Victory, however long and hard the road may be, for without victory there is no survival.

A month later, on June 4th, when the British army had been crushed and barely escaped from Dunkirk, leaving all its tanks and artillery behind, he said:

Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail.

We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be.

We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender…

Two weeks later, as France surrendered and Hitler’s forces began their preparations for the invasion of Britain, he said:

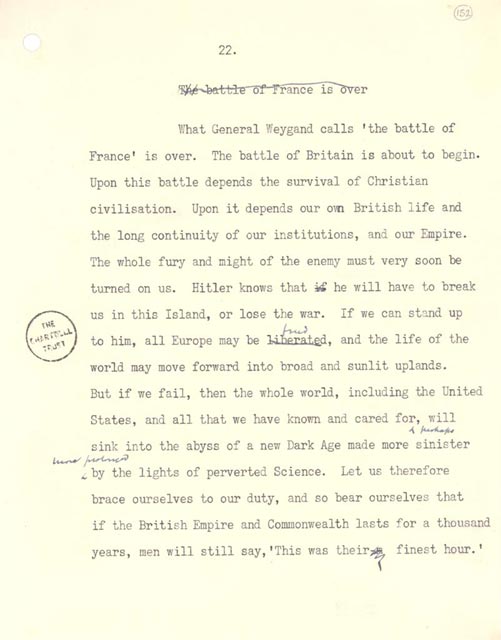

The Battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization. Upon it depends our own British life, and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire.

The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us. Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be freed and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands.

But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new dark age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science.

Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves, that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, “This was their finest hour.“

From Prose into Poetry

I think one of the secrets of the power of Churchill’s words may have been that they were composed as prose and then magically transformed and reformatted into poetry. Perhaps he heard his words, rather than saw them as words on paper, as he dictated them to his secretary.

Churchill was steeped in the tradition of Elizabethan English, the language of Shakespeare and the King James Bible, both of which were written, for the most part, in poetic form.

Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more;

Or close the wall up with our English dead. (Shakespeare, Henry V, 3.1)

They shall beat their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning hooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore. (Isaiah, 2.4)

These were words to be declaimed from the stage or from the pulpit, words not just to communicate with their listeners but to sweep away them away.

The following images show an early draft of Churchill’s ‘finest hour’ speech, as first written, and then in final form for his notes as he stood in the House of Commons.

Churchill is also universally acknowledged for his oratorical skills. Here is an interesting clip from his current successor (Boris Johnson is the 14th prime minister since Churchill) explaining Churchill’s use of language from that perspective.