Whirlwind: Origins and design

The Whirlwind could do what its competing Messerschmitt 110 heavy fighter could not do: it could outrun the best single-engine fighters and dog fight them too. Its four 20 mm cannons were unmatched at the time. It could, to borrow Mohammad Ali’s great expression: ‘float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.’

Ernest Hines, the brilliant head of Rolls Royce aero engines (a true unsung hero), wanted to scrap the Peregrine in order to focus on the Merlin but Wilfred Freeman of the Air Ministry (another of my heroes) told him to keep it alive to give the Whirlwind a chance of realizing its potential.

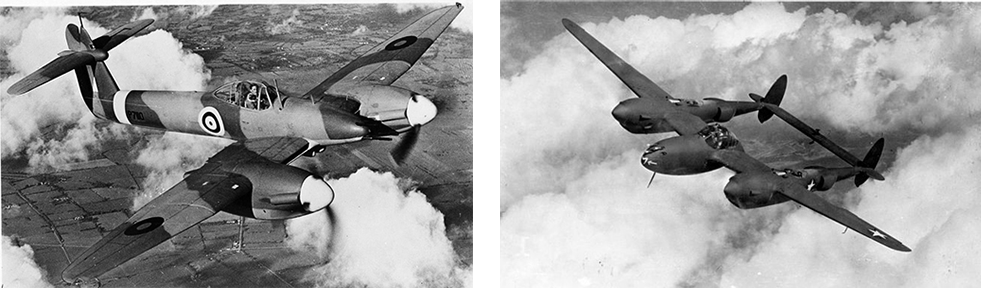

The Whirlwind was specifically designed to use the Peregrine and, unfortunately, changing to another engine would have required major alterations to the airframe. In addition, while the future of the Whirlwind was being debated in 1941 and 1942 the vastly superior and far more flexible Merlin-powered Mosquito was reaching maturity, and the Whirlwind faded into obscurity. Only 100 Whirlwinds or so were built (versus 7,000 Mosquitos) and only two operational squadrons were equipped with Whirlwinds.

To be fair, there is an argument to be made that the Peregrine was a far better engine than I have presented, and many of the failings I have described were actually caused by the way it was integrated into the Whirlwind airframe—its inadequate and poorly operating radiators, for example.

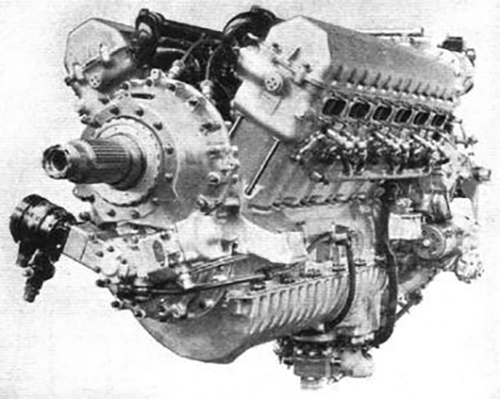

Alas, the dismal story of the Peregrine was not quite over. The Peregrine was a V12, with two banks of six cylinders driving a common crankshaft, producing an inadequate 885 horsepower. Ah ha! thought someone. Let us take another Peregrine, turn it upside down and add it to the crankshaft making an X24 with 1700 horsepower! This became the very problematic Vulture, an engine that powered the unsuccessful single-engine Tornado fighter and the unsuccessful twin-engine Manchester bomber.

The struggling Vulture-powered Manchester became the brilliant Merlin-powered Lancaster

Whirlwind: Operations

Alas for the Whirlwinds, supply and development priorities were always given to other aircraft and Whirlwinds never realized their potential. The vision of a big, tough, twin-engine single-seat fighter would eventually be fulfilled by the superb Lockheed P-38 Lightning.

Almost… …Quite

Whirlwind: Infinite Stakes

In spite of all its shortcomings the Whirlwind remains a fascinating ‘what if.’ In my novel Infinite Stakes my protagonist Johnnie Shaux test-flies the Whirlwind and runs afoul of the Peregrine’s defensive Roll Royce engineers.

“Double failure?” Bald Head asked. “What is a so-called double-failure?”

“At five thousand feet the starboard engine overheated, sir, and began emitting heavy black smoke. I shut it down. We subsequently identified a supercharger failure.”

Bald Head grunted.

“Then, as I was returning to Martlesham, the port engine began to overheat.”

“Began? How did you know?” Bald Head demanded. “What did the temperate gauge indicate?”

“I don’t know—I didn’t look at it, sir.”

“Then how could you possibly know the engine was overheating without looking at the gauge?”

“I relied on the flames coming out of the engine, sir.”

Johnnie loved the idea—the principle—of the Whirlwind, a petite, saucy-looking aircraft with a high tail and a vicious sting in its nose. The wings and chubby little engine housings were low-slung and far forward. The pilot sat high on the fuselage in a bubble canopy offering a superb field of vision. The Whirlwind was only 45 feet wide and 32 feet long, only slightly bigger than a Hurricane, but with much more punch and power. With its upright tail and deadly armament, Johnnie would have called it a ‘Scorpion,’ but there was doubtless a naming committee somewhere in Whitehall which decided such things; Hurricane, Tempest, Tornado, Whirlwind, Typhoon … he’d hate to have to pilot an aircraft named ‘Squall’ or ‘Gale.’

My next blog will feature another aircraft that fought hard but was not dominant, the Grumman F4F Martlet flown by the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm.