An aircraft for all seasons

One of the main characters in my new novel, Trial and Tribulation, is the De Havilland Mosquito. Unlike most of the other characters in the book, the Mosquito was—and is—very real.

One of the most interesting aspects of technology, I think, is how some designs are simply better than others—not just a little better, but dramatically better. Form and function combine to make something superior to other designs. One can think of Steve Jobs unveiling his miraculous iPhone design, for example, in comparison to the clunky flip tops and Blackberries of that time.

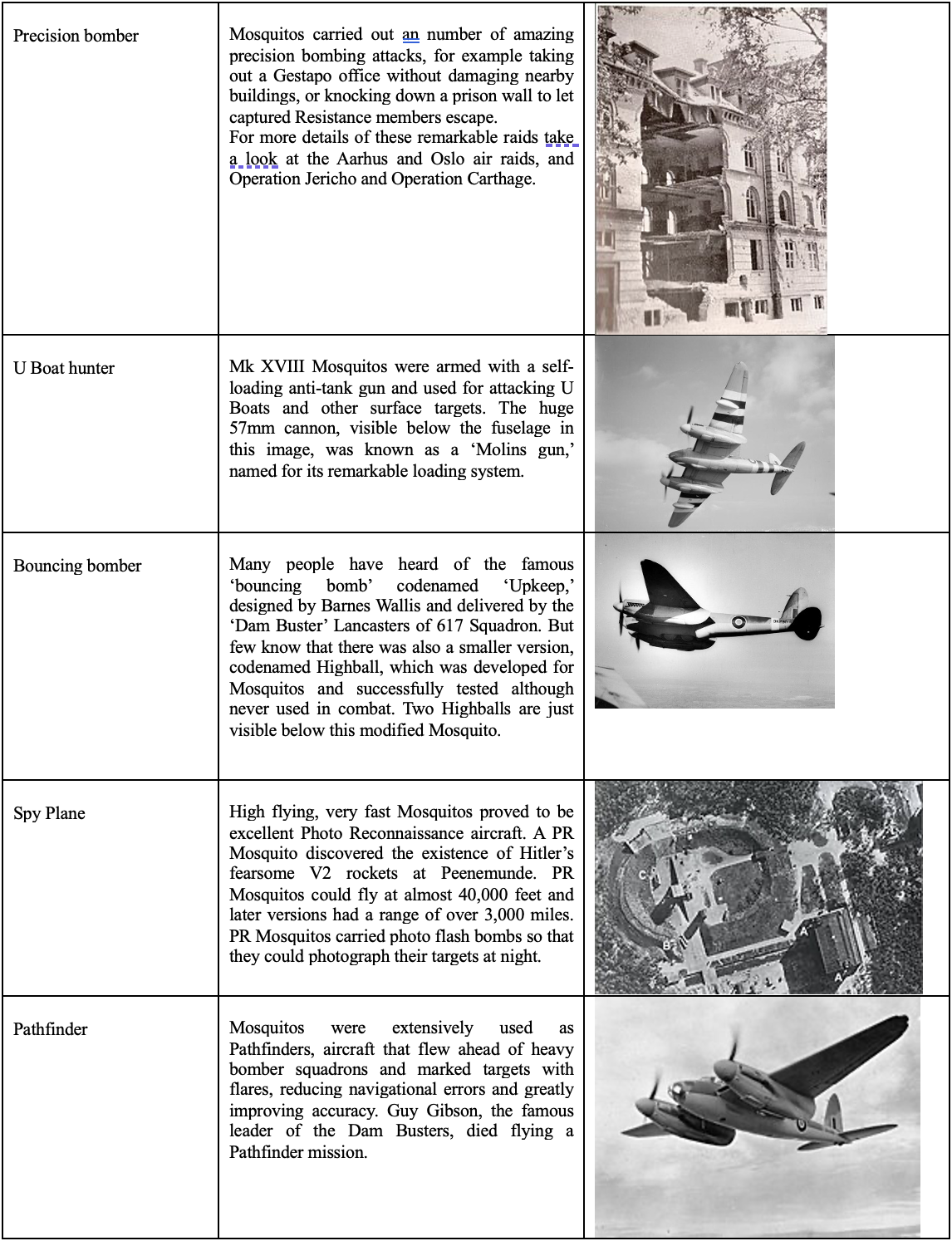

The Mosquito was such a design. It was totally unexpected, totally unconventional, and yet totally right. It was conceived as a bomber, and indeed it was a very successful bomber, but it was also an excellent fighter, reconnaissance aircraft, a powerful anti-U-boat attack aircraft … in fact, if you listed all the various roles for which aircraft military are designed, the Mosquito would come out as in the best two or three in that role.

To give just one example, in 1943 a B17—an aircraft I admire greatly—could haul a 4,000lb bomb to Berlin at a speed in the 220-mph range. A Mosquito could carry a 4,000lb bomb to Berlin about a 100-mph faster.

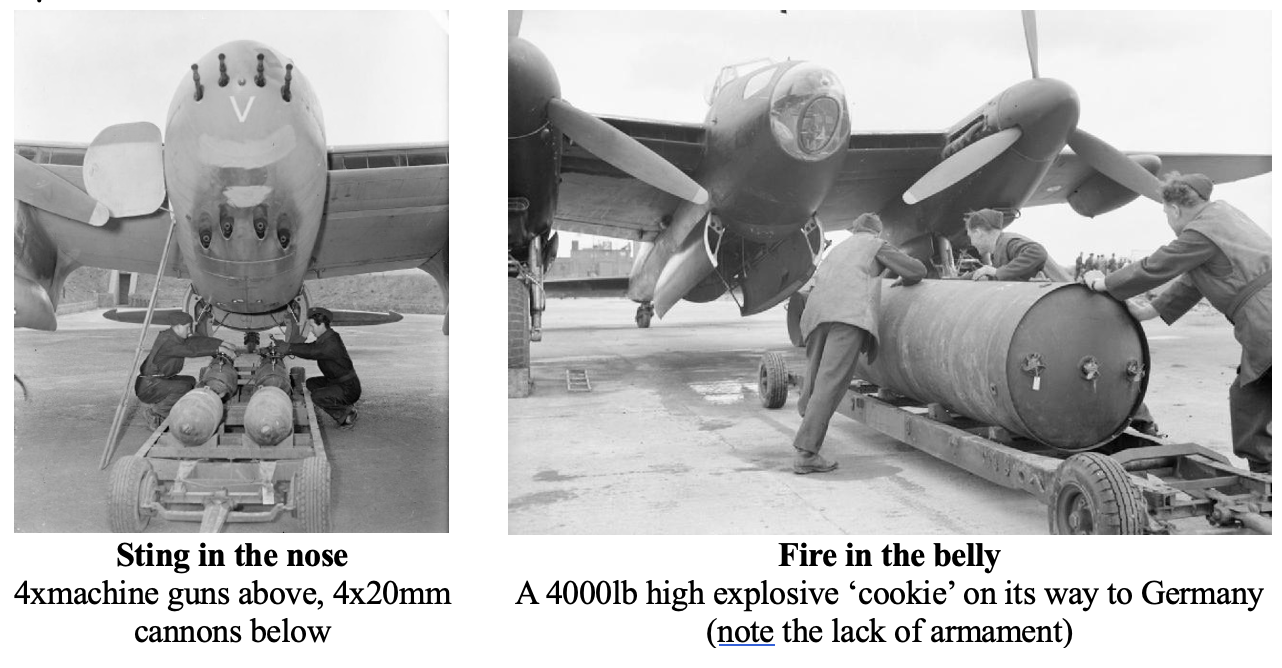

Well, one more example: the Focke-Wulf Fw 190 A8, probably the most fearsome Luftwaffe fighter of the era, typically had 2x13mm machineguns and 2x or 4x20mm cannons in various configurations. Guns firing through the propeller arc needed to be synchronized and those mounted in the wings needed to be trained to converge on their target at a designated distance. A Mosquito, on the other hand, had 4x20mm cannons and 4×7.7mm machineguns all clustered in the unobstructed nose firing straight forward along the axis of the aircraft directly ahead of the pilot’s eyes.

‘Freeman’s Folly,’ the ‘Wooden Wonder’

It is in the nature of all bureaucracies to reject good ideas, and the RAF and the British government duly opposed the original design of the Mosquito because it was … original. All modern aircraft were built from steel and aluminum. The proposed Mosquito was built from—gasp—plywood. All bomber aircraft of the era had to carry guns in moveable turrets to defend themselves from enemy fighters; the proposed Mosquito would carry … no guns at all. Indeed, the proposed Mosquito suffered gravely from original thinking in many ways.

The Mosquito was the brainchild of Geoffrey De Havilland and its Whitehall advocate was Wilfred Freeman. De Havilland built the airframe from mahogany and spruce plywood bent round formers, which proved to be immensely strong and yet flexible, and very light in comparison to metal. The fuselage and wings were stuck together with glue and needed no rivets; the skin was covered with silky-smooth doped fabric so that the aircraft slipped through the sky. The Mosquito was built in furniture factories and did not compete with other aircraft for skilled labor, steel or aluminum.

De Havilland gave the Mosquito two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines so that it was immensely powerful. The combination of raw power and light weight made the Mosquito as fast as any aircraft in the sky—a bomber faster than Luftwaffe fighters!

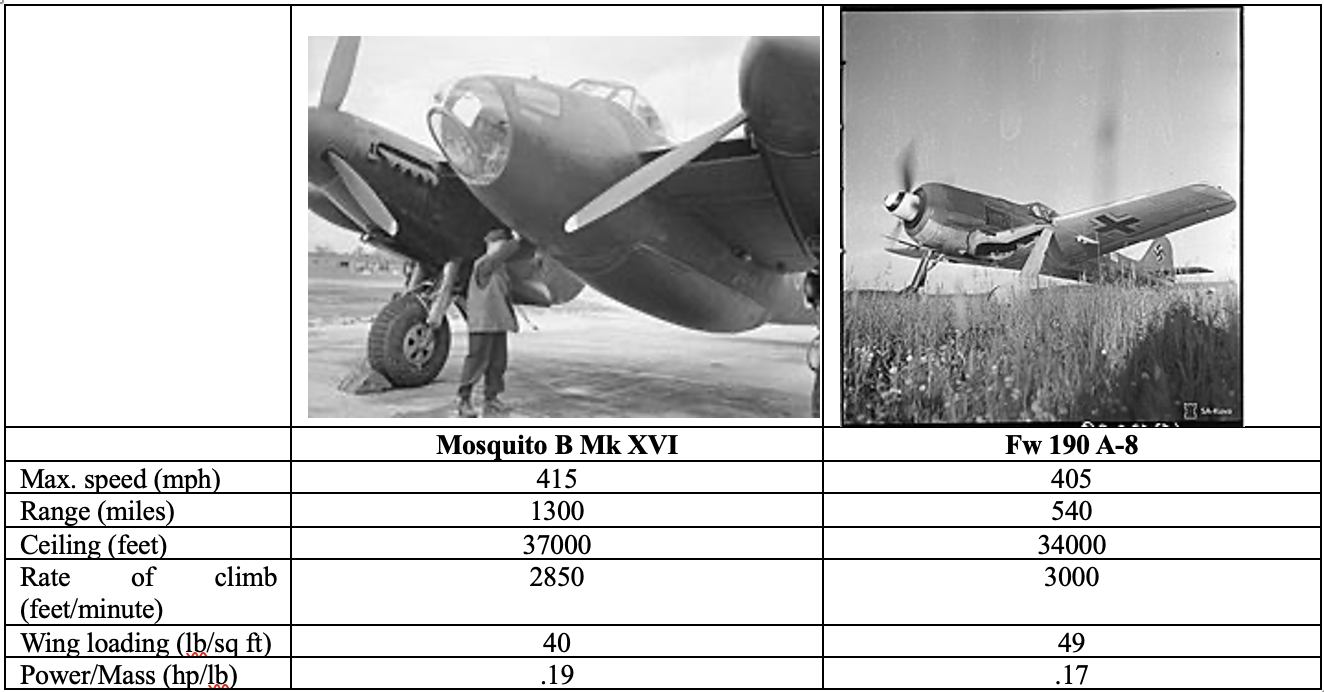

The following table illustrates just how extraordinary the Mosquito was. It out-performed or equaled the Fw 190, a purpose-built bomber-destroyer, in every category.

De Havilland built a prototype Mosquito despite official doubts and Freeman, who had also championed the Spitfire, overcame the naysaying bureaucrats. What Whitehall had lampooned as ‘Freeman’s folly’ became known as ‘the wooden wonder,’ and rightly so. Almost 8,000 were built.

The Mosquito stung Herman Goering

Herman Goering, the head of the Luftwaffe, was furious that the German aircraft industry had not been able to produce a comparable aircraft. He is widely reported to have said:

In 1940 I could at least fly as far as Glasgow in most of my aircraft, but not now! It makes me furious when I see the Mosquito. I turn green and yellow with envy. The British, who can afford aluminium better than we can, knock together a beautiful wooden aircraft that every piano factory over there is building, and they give it a speed which they have now increased yet again. What do you make of that? There is nothing the British do not have. They have the geniuses and we have the nincompoops. After the war is over I’m going to buy a British radio set—then at least I’ll own something that has always worked.

(On a personal note, I should point out one error in Goering’s tirade: I can attest that German radios after the war were much better than British ones!)

Goering had good reason to be furious. The 10th anniversary of Hitler’s accession to power was on January 30th, 1943. The Nazis planned radio-broadcast speeches to celebrate the occasion, one by Goering in the morning and another by Goebbels in the afternoon. Just as Goering was about to speak three Mosquitos flew over Berlin in daylight and bombed the radio station.

This was particularly infuriating for him because, in September 1939, he had promised the German people that no enemy bomber could reach Germany. “No enemy bomber can reach the Ruhr. If one reaches the Ruhr, my name is not Hermann Goering. You may call me Hermann Meyer.” (He was using Meyer, a stereotypical Jewish name, as an insulting slur.)

Mosquitos also returned in the afternoon to disrupt Goebbels’s speech.

An extraordinary record

In addition to its role as a fast, accurate bomber, the Mosquito could:

Mosquitos in Trial and Tribulation

One of my great pleasures in writing Trial and Tribulation was to be able to explore the capabilities of this truly remarkable aircraft, as seen through the eyes of my protagonist Johnnie Shaux, and I hope I’ve been able to convey some of its fine characteristics.

From Trial and Tribulation:

“Good question,” he murmured to himself.